Bernard Meehan – Keeper of Manuscripts, Trinity College (September 2014)

Last Friday I had the pleasure of opening an exhibition of art by Mags Harnett, Scribe2Scribe, which explores an imagined dialogue, written in the language of text messaging, between two scribes who are writing the Book of Kells. The exhibition, on display in the Trinity Long Room Hub until the end of November, is intended to provoke thought on the changes which have occurred in the communication of the written word over the past twelve centuries.

Over the years I have become accustomed to seeing re-creations of pages from the Book of Kells. Generally such work aims to be as close as possible to the original, and some artists are more successful in this respect than others. This tradition goes back a long way. In the 19th century, one of the principal exponents was Helen Campbell D’Olier. Everyone marvelled at her work, but many years later it became clear that her accuracy was achieved in a very simple way: she stencilled copies directly from the precious manuscript. More recently, Misae Tanaka, an artist from Tokyo, has produced very faithful copies of the major pages. She has great insight and energy and technical skills, to the extent that at first glance, it is easy to confuse her work for a photograph, and she has an openly reverential attitude towards the Book of Kells.

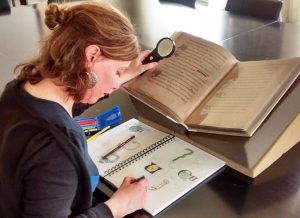

Mags Harnett working from the facsimile copy of the Book of Kells

Mags Harnett is quite different. She has produced a series of homages that are inspired by the manuscript but they are far from reverential. This is disruptive, and it makes us do a double-take at what seems familiar at first glance. We learn a lot about the Book of Kells from her work: we can see how the letters were formed; we learn that the monks were attacked by Vikings and left for Kells; and we learn that the scribes had cold hands; but we are also asked to believe that, for example, the Virgin Mary was in text contact with her son, and that is quite unsettling.

What Mags does is that she draws our attention to just how poorly we understand the book and its images. She mentions the difficulty posed by the language – by Latin – but the pictorial language and the way it works with the words is just as problematic. I feel that Mags has picked up brilliantly on the incongruity of how we look at works of art that we do not understand.

– Bernard Meehan

Mags Harnett was interviewed by RTE One’s Nationwide at Trinity College Library and the Long Room Hub:

Professor David Scott,Head of dept of French (Textual and Visual Studies) Trinity College Dublin, former President of the International Association of Word & Image Studies (September 2012)

The question of the relationship between word and image has been posed in European civilization since at least the time of the Greeks. This is because the West, having adopted the Phoenician alphabetic system rather than earlier pictograph or ideogrammatic models of the Egyptians, has tended to separate language from the visual image. This has led to a focus in Europe on concept (signified) rather than the agent of conceptualization, the (signifier) or image. This in turn has led to a separation of the logos from visual field: ’It is written’ becomes the criterion for truth, where visual representation is viewed rather as an illusion.This problem is one that has been central to my research as a specialist in word and image relations during my time in Trinity College Dublin over the last 30 years. It has led to the publication of a number of books exploring the issue in relation to poetry and painting, to graphic design (as in the poster and postage stamp) and to the visual arts (both abstract and figurative). So it is natural that Mags Harnett’s recent work should interest me, not only because she is one of my former students in Trinity College, but also because her work reflects an interesting aspect of the word/image problematic.

The word/image problem is one that became particularly acute from the Renaissance, as Modern European culture became increasingly heterogeneous as a function of the progressive over-layering of different cultural traditions. This meant that the seemingly more unified world of pre-Greek civilizations or indigenous cultures in other parts of the world – or even of the European medieval Europe world – became more complex: both Christian and mythical, both gothic and classic, both rational and spiritual, both textual and visual. The question of the status of the visual image in relation to language was therefore once more in the foreground of intellectual consciousness. But despite the invention of perspective and the perfection of techniques of mimetic representation in painting and sculpture, the visual arts were still essentially viewed as being secondary to poetry and literature. This was because language was still conceived to be the primary means of expressing truth – divine, rational or scientific.

A nostalgia for an integrated, synthetic, unified system of knowledge & representation, one that would integrate textual and visual media, has however persisted within the western tradition. The desire to return, at least on the level of art, if not on that of rational expression, to a more unified world in which word and image would be fully integrated again has become increasingly apparent in the modern period. This is why Indian and Chinese religious, philosophical and cultural traditions are viewed by some as offering a solution. Since the time of the early avant-gardes of the 20th century – Cubism, Futurism, Surrealism – the word or letter form has itself become a central motif in the work in modern European art. We can see this in the work of major artists of the second half of the century such as Jasper Johns or Cy Twombly. The aim of these artists is to rediscover in the word or letter as image or signifier – rather than as meaning or signified – new forms of visual expression, and, in particular, a reversal of the signifying chain in which colour, form and rhythm govern the viewer/reader’s response.

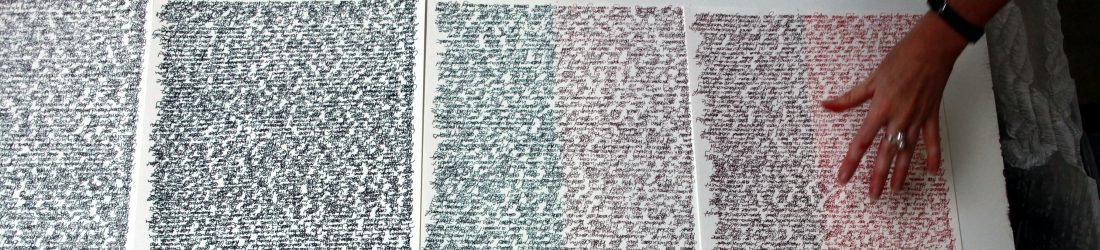

Margaret Harnett’s recent works on paper using pen and coloured inks explore precisely these possibilities. Though commencing as a writerly project with the pen used to write words and phrases on paper, it quickly becomes the form and rhythm of the writing itself that is the centre of interest, as the large sheets are covered with a picturesque scrawl. The graphic richness of the completed work is the result of the application of various methods: writing over on the same line or on a vertical as well as a horizontal axis, which creates a palimpsest effect; the splattering of rain or the influence of the sun in fading certain tones; the accidents of graphic expression, ink colour or density, the overlaying of graphic marks. These effects create unanticipated visual interest leading in the end to the pages being viewed overall as works of primarily visual art. At the same time, the overlaying of letters and words lose in the process nothing of their scriptural and graphic richness. Nevertheless, the question of the meaning of words or writing becomes secondary in these works which offer themselves up to appreciation in terms of primarily visual values – colour, richness and tone; rhythm, texture, spatial form.

So, to return to my opening remark, I think it is fair to say that in these wonderful new works, Margaret Harnett both turns on its head and yet maintains the validity for the visual arts as well as for language of the old criterion of truth: It is written. In doing so she makes an original contribution to our reflection on and our pleasure in the word/image problematic.

Opening Speech at the launch of ‘A Thousand Words’ Exhibition, The Copper House Gallery, Dublin 8.

Review of A Thousand Words in ArtHub Arts Journal

A thoughtful and eloquent review of A Thousand Words an Exhibition by Mags Harnett was posted in ArtHub.ie by writer Sue Rainsford. Describing the exhibition as a ‘hybrid cross-over of writing and visual art’, Rainsford reflects that ‘thought is prey to the same erosions as the body; a temporal, finite vessel for a potentially infinite medium’.